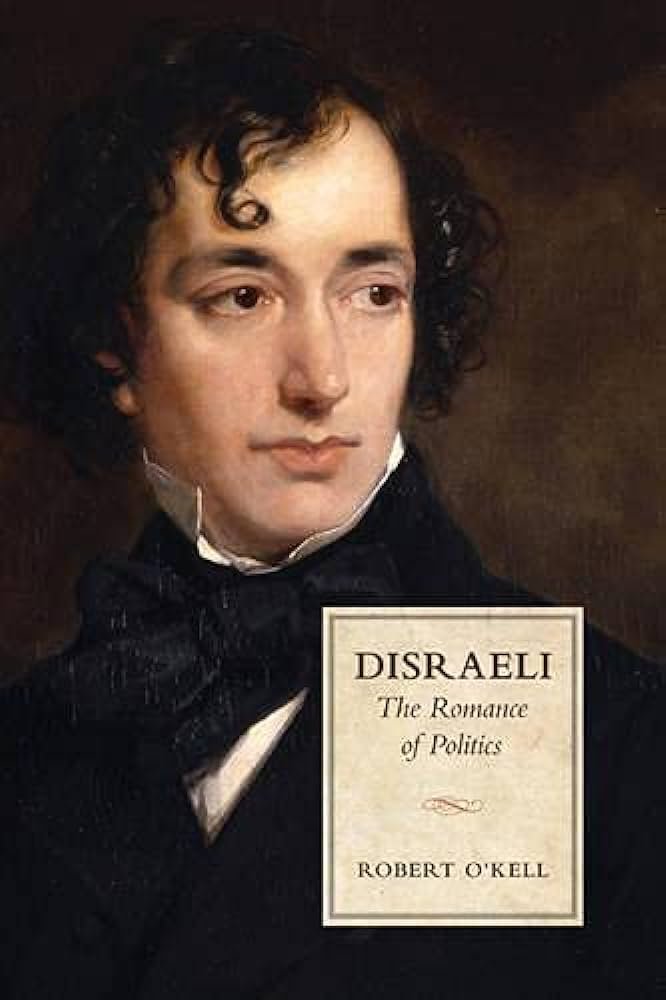

Book Review: Disraeli - The Romance of Politics

/Disraeli: The Romance of Politics

by Robert O'Kell

University of Toronto Press, 2013

The Victorian premiere Benjamin Disraeli – Chancellor of the Exchequer, Conservative Prime Minister, beloved confidante of Queen Victoria – is the subject of Robert O’Kell’s utterly fascinating new book Disraeli: The Romance of Politics, but the book isn’t a biography. Disraeli, although he joined the Anglican church as a child, was the first Jew to be Prime Minister, but O’Kell’s book isn’t an ethnological study. And throughout his life, in addition to pursuing politics, Disraeli was also a published novelist, but O’Kell hasn’t written a literary study of those novels. Instead, he’s blended all the old approaches to Disraeli into something groundbreaking, something very nearly as sui generis as Disraeli himself. We could almost call it psycholiterary biography.

Disraeli gained his first real foothold on the British public as a writer, not a politician, and throughout the 1830s he produced a string of novels – Vivian Grey, The Young Duke, Contarini Fleming, The Wondrous Tale of Alroy, Venetia, Henrietta Temple – the sternest courage begins to quail just at the list of them. In the 1840s he published his trio of so-called political novels, Coningsby, Sybil, and Tancred. There followed Lothair, and the torrent still had a few squirts left in it; after Disreali’s defeat in 1880 ended his political career, he turned straight back to writing, first resurrecting his half-finished novel Endymion and then beginning something that would probably have been called Falconet had it ever been finished (usually it was the books that died after about ten chapters; this time it was the author).

In the parlance of modern sports, Robert O’Kell has “taken one for the team” by plowing through these books; he’s suffered in his study annotating this stuff while his readers were blithely enjoying their third re-reading of Cranford. It was perhaps inevitable that a touch of Stockholm Syndrome would afflict him – Disraeli’s ghastly novels cast just this kind of spell over the more biddable elements of his contemporary readership, after all, so when O’Kell refers to the great gaudy mess of Tancred as “a slightly opaque novel of ideas,” his readers can nod in sympathetic pity at the understatement. When he compares the serial blunders of Lothair to Anthony Trollope’s Framley Parsonage, his readers can smile indulgently (less easy to overlook O’Kell’s frequent apologies for his subject – claiming Disraeli rejected the politics of Catholics but not actual Catholics, the politics of Chartists, but not actual Chartists, and so on). If they choose, those readers can focus instead on O’Kell’s often masterly overviews of his subject’s career, including its centerpiece contentions with the great Gladstone:

The most notable feature of that appointment, apart from the personal triumph of having overcome all of the obstacles to his success, was that it infuriated William Gladstone, who by this time was a complete convert to Peelite, small "l" liberal, economic doctrine, and who was convinced that it was his special destiny to reform the fiscal and monetary policies of the British government ... Thus, the stage was set for the great political rivalry that would come to dominate Parliament for the next thirty years.

But the novels are the key here, unbelievably, and there’s a method to the utter madness of plumbing their depths; the genius of O’Kell’s book is the way it gently prompts a re-assessment not of the merits of Disraeli’s fiction but rather its motivations. O’Kell holds that the books represent “an embodiment of [Disraeli’s] fantasies about himself,” that fiction offered "a form of compensation for failure or defeat by imagining transcendent success."

It’s nothing short of a revelation in insight, and it carries this marvelous book from beginning to end, throwing entirely new light on the frail heroisms of this ungainly, irresistible figure. Disraeli was a vocal Anglican, but he was also a proud Jew, famously retailing stories of how his ancestors, heroic Sephardim, fled from Spain rather than submit to the Inquisition, and O’Kell rightly points out the entrenched opposition that could greet a politician of Jewish descent in a Parliament that had excluded Jews until 1858 unless they swore an oath proclaiming the Christian faith. That Disraeli might have been in part using his fiction as an emotional release-valve for the pressure of his eternal outsider status in British society and politics is a stunning stroke of interpretation. On the one hand, O’Kell explains, “the novels are means of rationalizing the past and reshaping the formative experiences of his identity; on the other, they are a way of keeping the question of identity open by exploring imaginatively the possibilities of further commitment.”

The energetic merit of Disraeli: The Romance of Politics rests in this incredibly persuasive re-reading of the man; the danger of the book is that it might prompt the unwary to read the novels themselves. Any who might feel so inclined should recall the reaction of Boston Brahmin (and passable literary critic) Henry Adams when writing to a friend about Endymion:

"I have read Endymion, with stares and gasps. There is but one excuse for it; the author must have been in a terrible want of money; his tenants have paid him nothing, and Mr Gladstone has docked his pension. If he has not, he should. Endymion is a disgrace to the government, to the House of Lords, the Commons and the Jews."

Those readers might also recall that Disraeli got a whopping ten thousand pounds for the sale of Endymion (more, for example, than George Eliot got for all the sales of Middlemarch). That’s a bit of a reshaping formative experience all on its own.