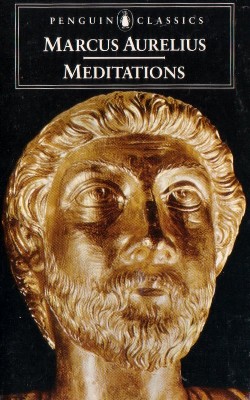

Verissimus

/Marcus Aurelius: A Life

By Frank McLynnDaCapo Press, 2009From kingdom to republic to empire, the ancient Romans have transfixed the imagination of the ages, inspiring bestselling novels, plays, poems, movies, and TV productions (not to mention several nations and more than a few dictatorships). Throughout 2009, we trace their pomp and circumstance in “A Year with the Romans.”

| Frank McLynn, one of our greatest living biographers, has written a big fat book on the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, praising him as a man for all seasons, and recently Mary Beard, one of our greatest living classicists, took him to task for it. Marcus Aurelius, she pointed out, fought border-wars, dabbled in memoir-writing, attempted some law reforms, and indulged in disastrous dynastic choices – so after all, in the roll call of emperors, hadn’t we better call him … rather ordinary?Were such a heretical suggestion uttered about, say, Elegabolus or Septimius Severus, the reactions would be limited to a handful of classicists and history buffs. But to make such a claim about Marcus Aurelius is to cause an outraged gasp that can be heard clearly in the apartment upstairs. For centuries, this emperor has been considered anything but ordinary – senators, statesmen, and dictators have claimed to know his little autobiographical sketch, The Meditations. Great men of every stripe have cited him as the very model of a virtuous prince, and even the notorious fictional mass-murderer Hannibal Lecter quotes him with respect. |  |

Happily, Mary Beard is one of those rare critics who’s perceptive enough to have her puckish fun. Quite apart from the perhaps misguided adulation American presidents and other miscreants have paid him, Marcus Aurelius was certainly not ordinary, and McLynn is well within his rights to spend so many pages giving us a new life of the man. Marcus Aurelius: A Life is nearly 700 pages long, and in addition to being McLynn’s best book (no mean feat in a career so filled with great volumes, it’s incomparably the best biography of its subject yet written.When that glorious dilettante classicist F. W. H. Myers offhandedly referred to Marcus Aurelius as “the master of a declining world,” he was both echoing the accepted thumbnail version of the man and indulging in the benign perspective of hindsight. Certainly Marcus himself would not have agreed with such a tag-line for himself – he dared not. He was born in 121 during the reign of Hadrian (who, remarking perhaps sardonically on his overly-serious nature, nicknamed him ‘Verimissimus’ – which means ‘the most truthful’ but can also be read as ‘the most annoyingly truthful’). His father was brother-in-law to Antoninus Pius, and when circumstances raised that good man to emperor after the death of Hadrian, both Marcus and his younger half-brother Lucius Verus were placed on the imperial path as Pius’ successors. In 161 Antoninus died and Marcus became emperor. He immediately commanded the Senate to grant Verus equal honors as his co-ruler.The empire they came to rule was seeded with perils that were not immediately obvious. When Hadrian’s imperial predecessor Trajan died, one of the first things Hadrian did as emperor was to pull back the legions from all the conquests Trajan had made during his reign – in Britain, in Parthia, all along the German borders. Hadrian ruled for twenty years, and Pius ruled for another twenty – by the time Marcus came to power, the results of that catastrophically stupid decision were in full flower: Rome faced massive, well-organized, well-disciplined antagonism from all her former imperial outposts, all at the same time.Dealing with war on every border is the stuff of an emperor’s nightmares, but Marcus would have slept peacefully if that’s all he’d had to deal with; such was far from the case. To a degree more pronounced than for any other Roman ruler, his time as master of the Western world was characterized by a non-stop struggle against all four of the Horsemen of the Apocalypse.Disease swept through the Empire during his reign, and that brought famine in its wake as whole countrysides were depopulated. War, as we’ve noted, was his constant companion. And death, that comes to emperors even as to common folk, was much on his mind, not only because being morose was a central tenet of the Stoicism he embraced but also because he was trying to make old bones (he died at 59) in a world without medicine (although he had the next best thing, the physician Galen). It’s small wonder that in all his portraits the emperor looks more than a little careworn.The central problem in reconstructing the life of Marcus Aurelius is the lack of good sources – and the governing presence of a bad one. Historians are forced to deal with the so-called Historia Augusta, a ramshackle collection of factoids and anecdotes that purports to be the 3rd century collaboration of six authors working from three or four major earlier writers but is very likely the work of one 4th century writer making up fictitious sources and trying, for reasons known only to himself, to pass his work off as that of an older committee. For as many questions as it raises, the Historia Augusta prompts almost unanimous response among contemporary scholars, who all comment on its style, or absence thereof, and silliness.The Historia Augusta is, alas, one of our few major sources for this emperor’s life and times, and the strongest thing that can be said against McLynn’s book is that he tends to make uncritical use of it in telling his story.Or perhaps that’s not the best way to put it, since it implies a lack of probity that’s nowhere to be found in this big, brilliant book. Perhaps better to say McLynn makes extremely critical use of the Historia Augusta – in telling the tale he wants to tell. Marcus Aurelius: A Life is very much an old-school biography; our author is not simply presenting us with a detached lecture on the known facts of Marcus’ life (as previous 20th century works on the man have done), he’s giving us those facts filtered through his own combative intellect and judgements. He has a broad-canvassed story to tell us, and he has vigorously held and fiercely defended opinions on every aspect of it. For such a passionate biographer, the Historia Augusta is heaven-sent, just perfect for selectively cherry-picking the stuff that best suits your dramatic purposes. We have Cassius Dio, a far more sober source, to balance against some of it, but McLynn’s reader must still proceed with some caution – if a story related in these pages sounds more personal and revealing than reliable ancient sources typically give us, it’s probably McLynn passing along something from the Historia Augusta in order to shape his drama. And I say more power to him; better by far a tricky book than a boring one.

|

This is an exciting, unstoppable read, and only occasionally is this effect achieved through lazy use of idioms (“Commodus was aware that his return to Rome after concluding such a controversial peace was a make-or-break affair, that he would not be able to please everyone, and especially not the ‘hawks’’; even the opinion of the Roman ‘chattering classes’ and professional philosophers inclined to the view that the settlement with the German tribes was a mistake” … and a few other lapses). Far more often, the vibrant immediacy of McLynn’s book comes from the best source imaginable: the author’s own endless enthusiasm for his subject matter. We get the facts of Marcus’ reign, and we get generous, spirited side-helpings on such connected topics as the state (and history) of the provinces, the empire before (and after) Marcus, the nature of 1st century medicine and culture, and the nature of the Stoicism that so informs The Meditations, the remarkable little book Marcus left behind to be tucked into saddle-bags at Waterloo and shoulder-bags at Camp David. McLynn has done an enormous amount of reading on all of these things, and he’s eager to distill it all for his readers, and his blasting enthusiasm never falters. If this threatens to exhaust his readers, well, it’s a happy exhaustion. |

Central of course is the life itself. Marcus Aurelius ended up spending nearly half his time as emperor fighting frontier wars away from Rome. But he was in all likelihood a mild, bookish man by nature, and at first he stayed in the City and sent Verus (his co-emperor and ten years his junior) out to wage the empire’s wars. Verus spent five years fighting in Parthia and was, as far as can be discerned, a good general and a fair administrator, but he has one big problem: the Historia Augusta doesn’t like him. Or rather, not so much doesn’t like him as wants very badly to make an object lesson of him by contrasting him unfavorably with Marcus. So if Marcus is studious and mild, Verus must be dense and profligate, and so he’s endlessly portrayed, including, alas, by McLynn, who characterizes him as a ‘teacher’s pet’:

Lucius Verus always had an amused contempt for learning and academia, but used his charm to bluff his way out of most situations… [he] was one of those popular, charismatic, yet ultimately empty-headed and second-rate personalities either in power or close to power that we encounter throughout history; many of the contemporary descriptions make him seem an uncanny pre-echo of Henry II’s son, Henry the Young King, a charming hedonist, spendthrift and profligate. He was extremely good-looking, tall and stately in appearance, with a forehead that projected over his eyebrow. Such was his vanity that he used gold tint to highlight his hair.

Verus is thus pressed into service highlighting Marcus Aurelius’ poor judgement of people: he insisted that this sot be made his co-emperor, he gave vast military power to Avidius Cassius, who then rose in rebellion against him, and finally, most disastrously, he failed to see what a monster his own son Commodus would be as emperor. The problem, as mentioned, is that you can’t trust the Historia Augusta as far as you can throw it (gold-tinted highlights?); better by far, if possible, to judge people by their actions. Avidius Cassius actually did revolt (that this was done against one of the mildest, most tolerant emperors in the history of the world prompted one official to write to Cassius simply, “You are mad”), and Commodus actually was a monster as emperor. But Verus? He prosecuted Marcus’ Eastern wars efficiently from 161-166 (he personally leapt no battlements, but then, if McLynn has personally leapt battlements, I’ll dance Swan Lake in a pink tutu), and he administered the peace no less efficiently – in every way his actions reveal him as a wise choice to act as the emperor’s proxy. It’s always irritated me that he doesn’t get his fair credit, but I suppose it’s natural: the good apple/bad apple storyline is too tempting.And Verus did make one horrible blunder, although unintentionally: it was almost certainly he and his victorious armies who brought ‘the Antonine plague’ back West. Soon, the Empire was reeling under the effects of one of the worst pandemics in recorded history.Estimates of mortality are notoriously hard to nail down, but something like ten million dead seems quite possible. McLynn expands on the vast and sudden manpower shortages such a calamity would have caused, and of course he’s done his due diligence as to that other favorite conundrum, the exact medical culprit involved. He plumps for smallpox, and he’s ready with the lingo:

Haemorrhagic smallpox, the most deadly kind, is accompanied by extenstive subcutaneaous bleeding, and bleeding into the mucous membrane and gastrointestinal tract. The bleeding occurring under the skin makes it appear black and charred. Death usually occurs five to seven days after the appearance of the illness, caused by massive haemorrhage in all the vital organs, though the proximate cause of death is heart failure or pulmonary oedema. The mortality rates are almost 100 per cent in the case of haemorrhagic smallpox and 90 percent in the flat type.

Once he gets going on this gruesome subject, of course, it’s tough getting him to stop (indeed, when he writes that one of Galen’s literary faults is “prolixity,” one must titter just a bit at the irony):

If we correlate all this with Galen’s observations, we can easily appreciate the high degree of probability of a diagnosis of smallpox for the pandemic of 165-180. With his usual care, Galen detected the presence of fever, even though this was not apparent to those who touched the patient. Stomach upsets were a constant feature of every case he investigated; there was vomiting, foetid breath, diarrhoea, the coughing up of blood and of the membrane lining the larynx and pharynx, internal ulcerations of the windpipe and trachea (which left the patient unable to speak) and, above all, the presence of black exanthema and black excrement.

(Quite a bit of gory detail, yes, but it sure is refreshing to see Galen used so intelligently).Whatever it actually was, this plague reached its ferocious peak in Rome in 166. Ever circumspect, Marcus gives the title of Caesar to his two heirs, five-year-old Commodus and four-year-old Annius, and in the following year he sets off for the Pannonian frontier in order to chastise the invading Macromanni and Quadi, most elements of whom withdraw at his approach (several of Marcus’ legions were inexperienced or undermanned, but McLynn is right to point out that the emperor was very likely still at the head of a massive amount of men and equipment). You can’t help but sympathize with Marcus at this point in his story, fighting valiantly and intelligently to push back invasions, to create and shore up alliances, to hold things together when everywhere they seemed determined to fly apart. Did he contemplate simply annexing rebellious lands like Dacia? “Whether he had already begun to think of the other possible solution,” Antonine scholar Albino Garzetti writes, “that of direct annexation, it is difficult to say, but Trajan’s conquest of Dacia was a precedent that could always be followed.”He never did it, and not just because the aforementioned revolt of Avidius Cassius hobbled his forward momentum – or even because the pith of his empire was rotting with plague. Most of his life from the death of Verus in 169 to his own death in 180 was consumed in warfare all over the Roman world. He’d no sooner win a great victory (and there were great defeats as well – thanks to the spotty records, we get only the echoes of what must have been epic struggles) in one theater than he’d have to quell an irruption of hostilities in another. We have seen what such unremitting pressure, access to such reflexive violence, has done to countless leaders throughout history. We have watched as so many of them became emptied of their humanity and filled with rage – as they became part of the darkness, rather than fighting it.That didn’t happen to Marcus Aurelius, and we may never know why not. Those who put their faith in innate character will say it was his nature that saved him from becoming the violent creature his son became. Those who look to philosophy for hope will credit the brand of Stoicism to which he adhered his whole life, which counseled continuous self-examination and restraint (even while it allowed him philosophical leeway for persecuting Christians during his reign). Those of us who prize the release of writing might like to believe that it was the upkeep of his little book (sometimes continued, it would have us believe, “among the Quadi”) that kept him constantly revising himself.Whatever the reason, he stayed a mild, conscientious person right through the worst his declining world could throw at him, and as his biographer points out, he tried his best to display balance and insight, even in acrimonious court decisions that had to be troubling to a man of his retiring frame of mind:

Above all, Marcus insisted on tolerance and a full avoidance of the tyranny of earlier emperors. He forbade his guards to drive away citizens who approached him with petitions. He allowed mime writers [sic] and satirists, notably Marullus, to lampoon him with impunity, making something of a fetish of untrammelled free speech, even when it involved scurrilous comments on his own person … But he liked to make it clear that, despite his tolerance and forebearance, he was no soft touch. When one of the defendants in a lawsuit protested vigorously against one of his judgements, on the ground that he had done no violence, Marcus replied, “Do you think it is violence only when men are wounded?”

| “Marcus’s record as emperor,” McLynn sums up, “though not perfect, was honourable. Most of all, he was unlucky.” But the emperor is lucky in his biographer – this book of McLynn’s is a brawling, over-spilling magnificent masterpiece, a old-fashioned Victorian triple-decker with full and fascinating digressions on whatever the Hell the author feels like expanding upon, every single paragraph alive with muscular learning and a smiling familiarity with life. The shy, ascetic Marcus of the hagiography (which began even in his own day and has survived long enough to be enshrined by Hollywood) would have been appalled, but the tenacious and indomitable flesh-and-blood man who held his empire together by force of will for twenty years would have wanted, I think, to buy McLynn a drink. |  The Triumph of Marcus Aurelius by Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo The Triumph of Marcus Aurelius by Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo |

The book is not without its flaws, of course. As noted, the Historia Augusta gets far more credence than any serious scholar has ever thought it deserved (reading some of its whoppers, you can’t help but think its author – or authors – would also have been surprised at McLynn’s confidence … “He actually let us get away with that?” you can almost hear them say). And like most men of vast reading and extremely athletic researching, McLynn has an armory of codified opinions, not all of which withstand scrutiny equally well (one that particularly struck me was his contention that there are only three “indisputably great” spiritual autobiographies in the history of the world: Rousseau, Newman, and Mill – a list which conspicuously omits two other contenders – and one saint).But any slight undercurrent of irritation such sureties might have produced in me by the end of Marcus Aurelius: A Life was completely wiped away by the book’s totally unexpected, incredible final gift to its readers – the author’s notes in the back. Here, in what would ordinarily be a bleak and forbidding forest of op.cit.s, is where McLynn displays the full breadth of his scholarship, not merely referencing every book, monograph, and article on the Roman world ever written in four languages but walking his readers through it all, as if to demonstrate beyond refutation that the notes themselves were not simply cobbled together by a team of graduate students. The whole thing forms a virtuoso coda to the enormity of the main work, and it shares plenty of that work’s signature traits. For instance, there are plenty of those same vociferous codified opinions designed to stir debate:

It is overwhelmingly probable – approaching certainty as a limit – that Marcus died of smallpox. This placed him as one of the first among many other rulers who would succumb to this disease, including Czars Peter II and Peter III of Russia, Elizabeth I of England, Louis XV of France, George Washington of the USA, Queen Mary of England, the Incan emperor Huanya Capac (in 1527), to say nothing of Rameses V of Egypt and three emperors of China (Kangxi, Shunzhi and Tongzhi).

I myself am unfamiliar with the Chinese gentlemen in question, but I can assure you – approaching certainty as a limit – that not all those others died of smallpox. But it’s fun trying to figure out why McLynn thinks they did (simple ignorance being by this point in the book untenable as a reason). And this by no means exhausts the fun! Our author is happy to relay old jokes:

This is not the place to revive the ancient Plato-versus-Aristotle controversy, which will always to some extent be a dialogue of the deaf or, to cite the old joke, ‘Fishwives who bawl at each other through windows across the street will never agree that they’re arguing from different premises.’

And he turns in quick, knowing assessments fit to make me cheer: “By far the best book on St Louis is Jacques Le Goff, Saint Louis (Paris 1996)” – even while they irritate me with misplaced criticism: “Amazingly erudite and scholarly, it has just one flaw: the astonishingly exiguous space given to the Mongols (whom Goff dismisses cavalierly as L’Illusion Mongole on pp. 552-5)” (When the work is finally translated into English, readers with no French will be able to judge for themselves).Constantly throughout these notes, the formulation “one is reminded” crops up, and it always ushers in something entertaining, “One is reminded of similar criticisms [of Hadrian’s homosexual liaisons] (albeit for heterosexual philanderings) of US president John F. Kennedy.” “One is reminded of one of Voltaire’s quips: ‘Physicians pour drugs, of which they know little, to cure diseases, of which they know less, into humans, of which they know nothing.’” “One is reminded of Lyndon Johnson’s famous dictum: ‘I’d rather have him in the tent pissing out than outside the tent pissing in.’” "One is reminded of Robert Louis Stevenson’s aphorism: ‘The mark of beauty’s in the touch that’s wrong.’”It’s true that a touch too often, McLynn alludes to America as though it were a distant – and unsavory – alien world, but even here he provokes ample, if inadvertent, chuckling:

In terms of sexuality, Commodus appears to have been the active partner and Saoterus the passive one (sodomite and catamite, respectively, in the old pre-PC terminology). I am told by one who knows about these things that in American usage Commodus would be ‘top’ and Saoterus ‘bottom.’

And ultimately, even this slightly affected befuddlement serves to ally him with his readers. I urge all such readers to explore every corner of these boisterous end notes, if only to stumble across complaints like this:

In some respects Artemidorus out-sexualised Freud. The penis, for example, can symbolise one’s parents, children, wife, mistress or brothers. It can symbolise eloquence or education (since both are fertile) and is also a sign of wealth and possessions, secret plans, poverty, servitude, enjoyment of dignity and respect and enjoyment of civil rights. It is therefore difficult to imagine what the penis does not signify…

Hard not to like a biographer in such a quandary.___Steve Donoghue is a writer and reader living in Boston with his dogs. He’s recently reviewed books for The Columbia Journal of American Studies, Historical Novel Review Online, and The Quarterly Conversation. He hosts the literary blog Stevereads and is the Managing Editor of Open Letters Monthly.Join the Open Letters Facebook pageReturn to the Main Page