Vain Offerings

/The Year of Living Biblically: One Man's Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible

By A.J. Jacobs

Simon & Schuster, 2007

There is no explicit biblical injunction against writing fatuous, self-serving vanity-books, and this is lucky news for A.J. Jacobs, else he might be accruing trouble in some high places.

Readers will remember Jacobs’ previous book, The Know-It-All: One Man’s Humble Quest to Become the Smartest Person in the World, in which he fatuously, self-servingly set himself the task of reading the entire Encyclopedia Britannica from aardvark to zero and then telling everybody all about it. There’s nothing inherently wrong with reading the Britannica all the way through as though it were a textbook, although even a hundred years ago the essential imbecility of the task was so evident as to form the basis for a charming little scene in Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Adventure of the Red-Headed League,” where the hapless Jabez Wilson elicits uncontrolled laughter from Holmes and Watson by admitting that the League had conscripted him to undertake that very task. The reason for the derision is the same then as now: the task is so obviously reductive, so blatantly, simplistically moronic, that it’s mere undertaking renders the volunteer in question instantly pathetic. Jabez Wilson takes affront at the laughter of Holmes and Watson; how much nicer the world would be if A.J. Jacobs had a similar amount of self-regard.

Because he doesn’t just embark on these idiotic, childish quests, he writes about them. That’s the real corncob in the crankcase: some savant at Simon & Schuster saw the least-common-denominator potential appeal of The Know-It-All, and it became a best-seller, tucked into innumerable briefcases by men and women who bought into the basic premise of the book, that actually learning about anything is simply too much to ask a busy young professional on the Upper West Side—better by far to pick and parrot. And as a result of that book’s success, a success spurred on by an invitingly pedestrian prose style and the author’s characterization of himself as an aw-shucks everyman, we have this present book, in which the author comes up with the idea of trying to live literally by the Bible for one year. And then write all about it.

The Year of Living Biblically is a virtually genetic lock on the best-seller list. It will sell thousands and thousands of copies to people all across the country who’ve more or less entirely imbibed the Bush-era conception that expertise, that actually studying what you’re talking about until you understand it, is a thing ordinary people can’t be expected to have the time to do—or the desire to do, since in our current national environment painstakingly studied knowledge has a vaguely disreputable “Old Europe” air.

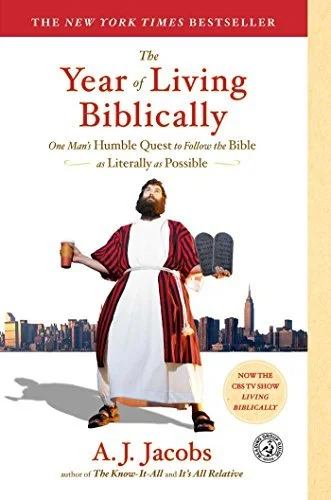

This cod liver oil would go down a lot easier if it didn’t smell so strongly of Simon & Schuster PowerPoint marketing sessions (the presence of that “humble” in both subtitles smacks strongly of market-brand mentality). As it is, all non-moronic readers will be feeling an undertide of dissettle after less than a dozen pages. In fact, the unease starts pretty much immediately with the book’s cover, showing the author dressed like a background extra from something by Cecil B. DeMille, holding a Starbucks-style coffee cup in one hand and a Ten Commandments-style pair of stone tablets in the other, eyes pitched heavenward with an innocent expression. This creates a false opposition right from the start, implying as it does some fundamental conflict between modern Western culture and devout religious practice. Looking at such a cover, the reader might suspect that Jacobs isn’t interested in talking with the millions of ordinary non-fanatical people in the world who try as hard as they can to honor whichever religious creed they’ve chosen to believe—the reader might suspect that Jacobs simply doesn’t believe he’ll find such people waiting in line for their morning coffee...after all, if they care about the one they can’t really care about the other, right? And this first impression is born out by the book: Jacobs spends virtually no time with everyday religious people. He subjects his wife and young son to the increasing eccentricities of his marketing gimmick quest (unruly beard, alien eating habits, etc), but he doesn’t bother to ask them what they think about God, or what constitutes righteous living. Why should he, after all, when the world still includes Amish he can go and bother? Honestly, if the Amish started charging admission every time some eager beaver with a book-idea came knocking (Christopher Hitchens, pay up! Daniel Dennett, we take cash or credit! Richard Dawkins, there’s a surliness surcharge!) they’d be richer than casino Indians.

The reason Jacobs gives his readers for why he tracks down such people as the Amish (he also spends time with the world’s tiny community of honest-to-God Samaritans, they of “good Samaritan” fame) is that they represent vivid examples of the challenge he’s imposed upon himself: to live “the entire Bible, without picking and choosing,” to follow Biblical injunctions as literally as possible and let the personal chips fall where they may.

But that’s just the reason he gives his readers. The real reason becomes apparent almost from the first page of The Year of Living Biblically and crops up with such regularity that it’s impossible to miss. Oh, our author does his best to mitigate it, palavering on in his aw-shucks manner about the perils of agnosticism:

The influence of the Bible—and religion as a whole—remains a mighty force, perhaps even stronger than it was when I was a kid. So in the last few years, religion has become my fixation. Is half the world suffering from a massive delusion? Or is my blindness to spirituality a defect in my personality? What if I’m missing out on a part of being human, like a guy who goes through life without ever hearing a Beethoven symphony or falling in love? And most important, I now have a young son—if my lack of religion is a flaw, I don’t want to pass it onto [sic] him.

(Even this early in the book, the careful reader will be suffering from exasperation exhaustion, whether it be from that hilariously ignorant “and religion as a whole” afterthought, encompassing, one supposes, the three billion humans on Earth who believe something other than the Bible, or from that “half the world,” as if Jacobs lives in a world that has four and a half billion agnostics, or from that bit about hearing a Beethoven symphony, which inadvertently condemns Jesus, St. Augustine, Bach, and heck, Beethoven himself)

But his numerous asides hint at his real reason, as when he’s reminiscing about his childhood: “It’s not that my parents badmouthed religion. It’s just that religion wasn’t for us. We lived in the 20th century, for crying out loud.” Or when he’s extrapolating what his quest will make of him:

Many of the rules will be good for me and will, I hope, make me a better person at the end of the year. I’m thinking of: No lying. No envying. No coveting. No stealing. Love your neighbor. Honor your parents. Dozens of them. I’ll be the Gandhi of the Upper West Side.

(I know exactly what you’re thinking about that last line. I won’t break the news to Jacobs if you don’t) Or when he quips that he wants to live as his Jewish forefathers did and then adds “but with less leprosy.”

No, the real reason for his quest, the real thing fuelling the marketing, is Jacobs’ obvious (although perhaps not conscious) belief that deeply religious people are inherently crazy, and that viewing them up close will be a reliable source of secular amusement, like looking at the lions in the Tower of London, or going to gawk at the madmen in Bedlam. As with those bygone amusements, so too with Jacobs: the moral atrocity of what he’s doing seems never to occur to him.

So it’s on with the antics. Seized by his “fixation,” he goes out and buys a literal stack of Bibles of all shapes and translations, buys another stack of Biblical commentaries online, assembles a “board” of spiritual advisors, never stopping to think that ordinary individuals trying to grapple with scriptural meaning don’t have his Know-It-All royalty checks with which to do all these things: the very steps of his preparation have already rendered any possible conclusions he reaches irrelevant, but that hardly matters—there are talk shows to attend!

Not that he isn’t cautioned by the genuinely religious people in his life, most of whom point out what a shallow and wrong-headed thing his “quest” is. And he’s appropriately melodramatic about his own doubts:

I felt torn, anxious about my approach, my monumental ignorance, my lack of preparation, about all the inevitable blunders I’d make. And the more I read, the more I absorbed the fact that the Bible isn’t just another book. It’s the book of books, as one of my Bible commentaries calls it. I love my encyclopedia, but the encyclopedia hasn’t spawned thousands of communities based on its words. It hasn’t shaped the actions, values, deaths, love lives, warfare fashion sense of millions of people over three millennia. No one has been executed for translating the encyclopedia into another language, as was William Tyndale when he published the first widely distributed English-language edition. No president has been sworn in with the encyclopedia. It’s intimidating, to say the least.

But quotes like this set a tremor of doubt in the reader’s mind, and quotes like the following, referring to the trip he and his wife make to Lancaster County to bother the Amish, only make deepen the doubt: “The trip takes four hours. Incidentally, I’m proud to say that I have absolutely no urge to make a double entendre when we passed Intercourse, Pennsylvania, which I see as a moral victory.”

The doubt such sentiments raise is the death-knell of any serious book: they inevitably make the reader wonder if perhaps the author in whom they’ve trusted their time and attention might in fact be an idiot.

Or worse: that he’s coldly, methodically writing for idiots. Specifically, for the idiots who were too busy or too gimmick-biddable to notice the sham at the heart of The Know-It-All. In that book, the mindlessly consecutive concatenation of raw data is dressed up to masquerade as the acquisition of knowledge. In The Year of Living Biblically, the spotty following of obsessively listed rules and prohibitions is dressed up to masquerade as a search for the meaning of faith. In both cases, the thwack of the fraud hits like the flat of a frying pan: the trick is to take work out of the equation. “The Four-Hour Work Week,” “The Twenty-Minute Workout,” “The Fifteen-Minute Diet”...work is anathema to the American book-buying public, and if A.J. Jacobs has one abiding deity, it’s the American book-buying public. They’re who he prays to, for the twin benisons of chit-chatty renown and a financial bottom line that allows him to buy stacks of Bibles and jet off to Jerusalem.

And what thoughts go through his head while he’s praying in Jerusalem? A better man than Jacobs would have been ashamed to write them:

I have my head bowed, and my eyes closed. I’m trying to pray, but my mind is wandering. I can’t settle it down. It wanders over to an Esquire article I just wrote. It wasn’t half-bad, I think to myself. I liked that turn of phrase in the first paragraph.And then I am hit with a realization. And hit is the right word—it felt like a punch to my stomach. Here I am being prideful about creating an article in a mid-sized American magazine. But God—if He exists—he created the world. He created flamingos and supernovas and geysers and beetles and the stones for the steps I’m sitting on.“Praise the Lord,” I say out loud.

It’s grimly fascinating to read such a passage and attempt to calculate just how offensive it is, and to how many different people. It insults Jews, of course (as does this entire book, from the cover photo on), by importing such blatant oafishness into the saddest of all their sad shrines. Less importantly, it also insults Esquire readers, and through them all of business-class young America, Jacobs’ very target audience. But most centrally it insults believing people everywhere with its dumb-show antics aping faith. If Jacobs had decided to spend a year as a cancer patient, if he’d written a cheery book describing how he’d hop into his hospital bed and act drained and uncomfortable, all done in front of people who are genuinely ill, the affront would not have been greater.

This pantomime continues for some 300 pages, and the sense of gimmicky manipulation is present on every page. Our author checks his sales ranking on Amazon and then wonders if it’s vain to do so. He covets Jonathan Safran Foer’s speaking fees and then mildly castigates himself for doing so. He tells us he’s trying to live the entire Bible, “without picking and choosing,” then a few pages later he tells us: “I’ve decided I can’t do that. That’d be misleading, unnecessarily flip and would result in permanent bodily harm and prison time.” He doesn’t seem to notice how many truly religious people throughout history have suffered both those things, and he certainly wouldn’t understand why. After all, royalty checks don’t do you any good in jail, and as for dying, pshhht! It’s the 21st century, for crying out loud.

It would be one thing if all this flippant hypocrisy were the agonized result of a genuine effort to apply the Bible literally to Jacobs’ life, but since he admits he’s going to pick and choose as he likes, the teeth of any such conflict are pulled before the book is 30 pages old. At one point his young son Jasper hits him in the face and refuses to apologize:

“Apologize.”“No.”This is going to be ugly.The Hebrew Bible says that hitting your parents can be punishable by death. Instead, I turn the other cheek.

But Jesus certainly wasn’t talking about children when he urged his listeners to turn the other cheek, and the Hebrew Bible doesn’t say hitting your parents can be punishable by death, it says it is punishable by death. By skating around this and other similar dilemmas, by in effect living only a bit biblically, Jacobs is able to spend a wild, wacky year dressing funny and writing a fizzy, harmless book.

He finishes his year and marks the occasion by ceremoniously shaving off his beard, an event at which there’s a professional photographer and a publicist who uncorks champagne (which combine to reveal Jacobs’ claim that he’ll “be back to being a regular old unremarkable New Yorker” as a fairly obvious bit of theater), and he spends the final pages of his book opining on how his year has affected him, but nothing so awkward or untidy as an actual religious awakening ever happens. The bored, supercilious agnosticism with which he begins his year of living a bit biblically is still firmly in place at its end, just as The Know-It-All ended with our author still the amiable amateur he was when he set out to read the Britannica.

But there’s a dire difference between the two books, despite all their surface similarities. The Encyclopedia Britannica is a secular reference work—as Jacobs so helpfully points out, communities do not live for it, and people have not died for it. The Bible is the polar opposite, a religious text of explosive history and power, a book that has been and remains the focal point for all that is good and all that is evil in the lives of millions of men and women. Which is not to say jokes can’t be made at its expense (Ken Smith’s Ken’s Guide to the Bible is often quite funny, and Monty Python’s The Life of Brian is the most hilarious movie ever made), but Jacobs isn’t joking, or at least he wants his readers to believe he’s not, and the Bible deserves better treatment than his prankish prancing. Every person who’s ever tried to live by any of its tenets deserves more than his artful lying about the year in which he says he tried to do likewise.

As mentioned, this book will sell well. It’s patterned closely enough to its predecessor to insure this. We can only hope Jacobs gains some kind of perspective on all this renown before he dashes into his next book, because The Year of Living Green would be boring where this book is sacrilegious, and The Year of Living Fat would be cruel where this book is trite, and The Year of Living Muslim might get him blown up in his car. This reviewer’s advice to our author: invest some of those bestseller profits, take a few years off from writing these silly, stupid books, and actually study something. It’s an unsettling experience at first, but you’ll get used to it.