Yet More (e) Book Snobbery in the Penny Press!

/Imagine a scenario: you’ve been given the task of hiring somebody for a position in your company. You collect applications, scrutinize resumes, do background checks for any indication of participation in the violent insurrection on January 6 designed to overturn a national election, execute the Vice President, and install Donald Trump as an unelected President-for-Life, and so on. But you realize that all such due diligence can only get you so far. What really counts are those personal references. So you make the phone calls, set up the times to talk, and one particular resulting conversation really stops you. This person seems intelligent and reasonable, and in the course of your conversation they’re very calmly, very methodically giving you reason after soft-spoken reason why your potential new hire would be a disastrous choice for your company.

Then about 30 minutes into your conversation, this surprisingly negative personal reference offhandedly mentions that they’ve always deeply hated your potential new hire, that they hated your potential new hire long, long before they ever worked together, that they think there’s just inherently no way your potential new hire could ever be worth a pan of cold mud, that they just HAAAAAATE your potential new hire, and another thing …

You’d end the call in about ten seconds, yes? You won’t be irrational enough to hire your new prospect solely because of that weird call, but you’ll almost certainly be furious that your time was so completely wasted.

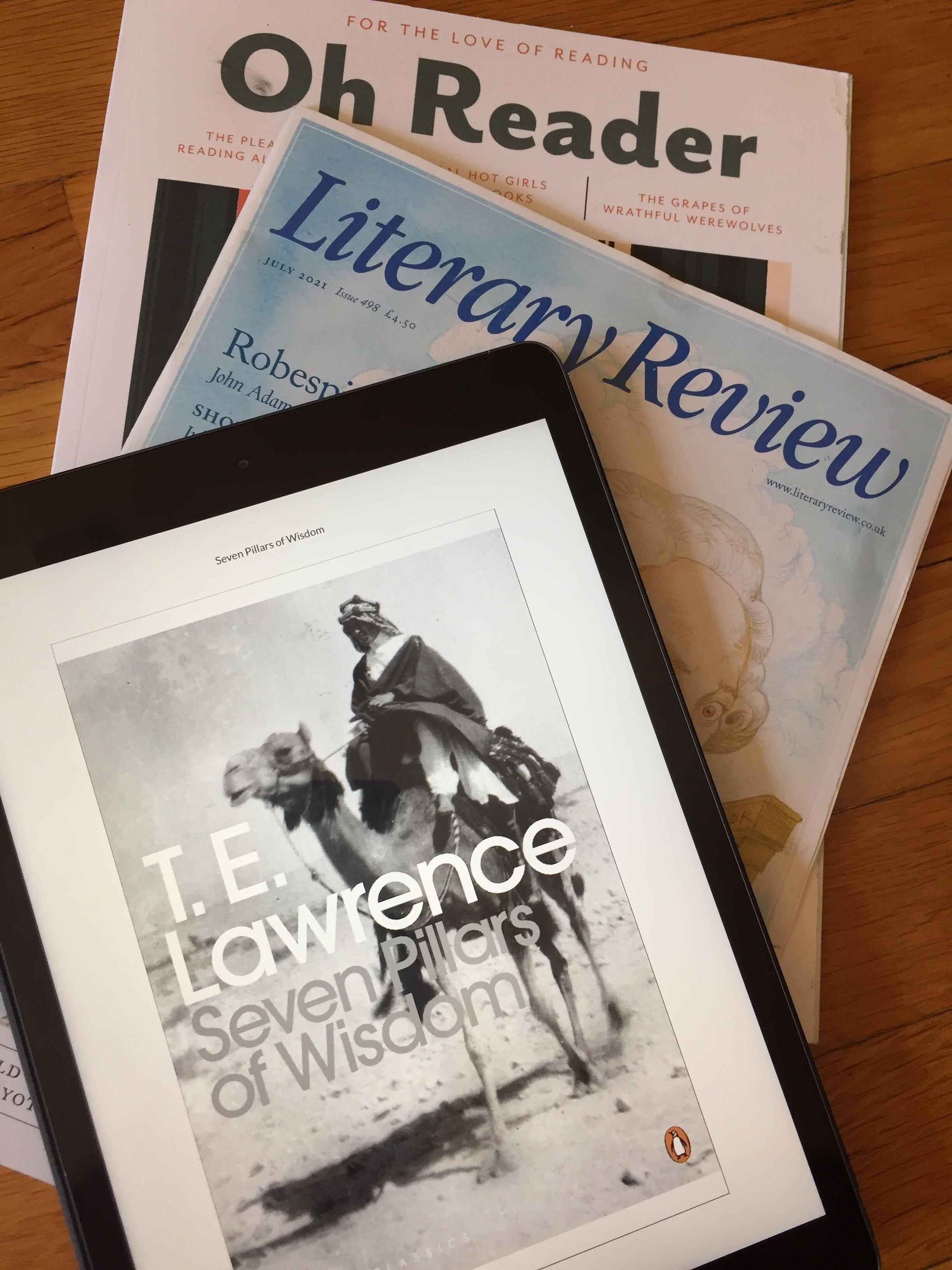

Which brings us neatly to “EBooks Are An Abomination,” a mid-September piece in the Atlantic by Ian Bogost. As the title suggests, this is yet another screed against electronic books, and it bears the subtitle “If You Hate Them, It’s Not Your Fault” - which, as we’ll see, is both true on one level and deeply, deeply untrue on another.

Because Bogost isn’t just bashing e-books for all the usual reasons book snobs tend to bash e-books. Bogost rehearses a few of them in this article: e-books are mechanically antiseptic; e-books don’t have facing pages or any of the other manifestation of what Bogost calls book typography; many e-books have become absurdly expensive; e-readers require electric charging, and so on.

Some of the faults Bogost attributes to e-books don’t exist - the thing would hardly qualify as a screed if it weren’t factually inaccurate at least some of the time, right? He claims, for instance, that “bookmarking and highlighting remain the only counterparts to dog-earing and marginalia.” Leaving apart the fact that a series of three gerunds calls for a fourth - “annotating” instead of the noun “marginalia” - there’s also the facts: bookmarking is dog-earing, and in addition to highlighting, annotating is not only possible with e-books but infinitely superior to the version that’s possible with printed books. E-book annotations aren’t limited by the miserly size of the page - they can scroll on at book-length. And since they’re typewritten, they don’t require deciphering. And since they can be exported to your email or a separate file, they don’t require finding.

There’s also skimming, which Bogost, for reasons known only to his fellow pedants, considers “the foremost feature of the codex.” It’s just faintly possible that an editor who considers skimming the most important aspect of reading is telling us more about himself than about books, but in any case, it’s entirely possible to skim in an e-book. Why you’d so all-fired want to is another question.

But his quibbling about the defects of e-books is quickly revealed to be at best adjacent to his main point. His main point is that hates e-books anyway, just HAAAAAATES them, and has hated them since long before they were applying for this job.

And the reason why he hates them? Simple: he’s a book snob. Hence the lie in that sub-title: the real reason you might hate e-books is because you’re cursed with genetic superiority. You hate e-books because you’re better than e-books.

“Whether you love or hate ebooks is probably a function of what books mean to you, and why,” Bogost writes. “What any individual infers about their hopes and dreams for an e-reader derives from their understanding of reading in the first place.” To hammer home the pinky in the air, he adds, “You can’t have books without bookishness.”

And who defines bookishness? I’m sure you’ll be astonished to learn: it’s Bogost himself. He tries to define what a book is, in its essence, eventually deciding it’s a group of bound pages made of paper (or something “akin to paper,” for all you anthropodermic bibliopegy fans) and extending to a certain length. Sure, for a thousand years in ancient Rome, for instance, that wasn’t true, but what’s a few thousands years to a book snob? If you’ve got the cobbles to imply that Virgil, Livy, and Cicero lacked bookishness, you’ve got the cobbles for just about anything.

No, the essence of a book is its form, and Bogost considers the printed book of the last 500 years to be a super-invention of human civilization, on par with “roads, mills, cement, turbines, glass, and the mathematical concept of zero.” If a better version of this particular mouse trap were going to come along, he writes, it would already be here. “In other words, as far as technologies go, the book endures for a very good reason,” he concludes. “Books work.”

Except when they don’t. You can’t read a printed book in the dark. If you encounter a word or phrase you don’t understand, a printed book offers you no help other than the hard scrabble of context. If a printed book snaps shut, you lose your place and need to find it again. Your printed books take up shelf space, strain floor-boards, gather dust. As noted, your printed books zealously guard your marginalia from your own use. Your printed book is only itself alone, and when you want another printed book, it’s inevitably across the room, or across town, or already checked out at the library (which is likewise across town).

But it turns out it’s not the fact that “books work” that makes them so attractive to Bogost. It all breaks down to data, you see: e-books are extremely compatible with a particular kind of bookishness, according to Bogost. It’s a kind of bookishness that “prefers direct flow from start to finish over random access,” one that “reads for the meaning and force of words as text first, if not primarily” … one that, and you surely saw this coming a mile away, “corresponds particularly well” with fiction in general and genre fiction - such as mysteries, sci-fi, young-adult fiction, and romance - in particular.”

And as if that kind of snobbery weren’t blatant enough, Bogost makes it even clearer: “I hate ebooks because I don’t read genre fiction, but I read a lot of scholarly and trade nonfiction … as a somewhat haughty book person, I also can’t wrap my spleen around every book looking and feeling the same, like they do on an ebook reader.”

In other words, the lie of that sub-title is in fact the oldest lie of all book-snobbery: if you like ebooks (earlier it would have been paperbacks, and before that machine-printed books), that’s because you’re not really a reader. It’s not your fault, you poor genre-loving slob; it’s just your nature. And if you hate e-books, well, that’s not your fault either: you’re just inherently superior. It’s a burden, really.

Noxious, to say the least. Leaving aside what value Bogost can possibly be extracting from “scholarly and trade nonfiction” if he’s so busy skimming it all, his objections to e-books boil down to simple, boring elitism: e-books are only read by the wrong kind of readers, indulging in the wrong kind of “bookishness,” reading the wrong kinds of books. Sub-human creatures worthy of Bogost’s parting condescension: “If you like ebooks, great. Enjoy your dim, gray screen in peace.”

E-book screens are not, of course, dim and gray. Most e-readers have bright, warm background light, and iPads can be quite colorful. Could e-books and e-readers be improved? Certainly. Are e-book fans a knuckle-dragging underclass fit only for slopping up plot-driven penny dreadfuls while their betters skim through art books? Ask your e-reader to define “prig.”