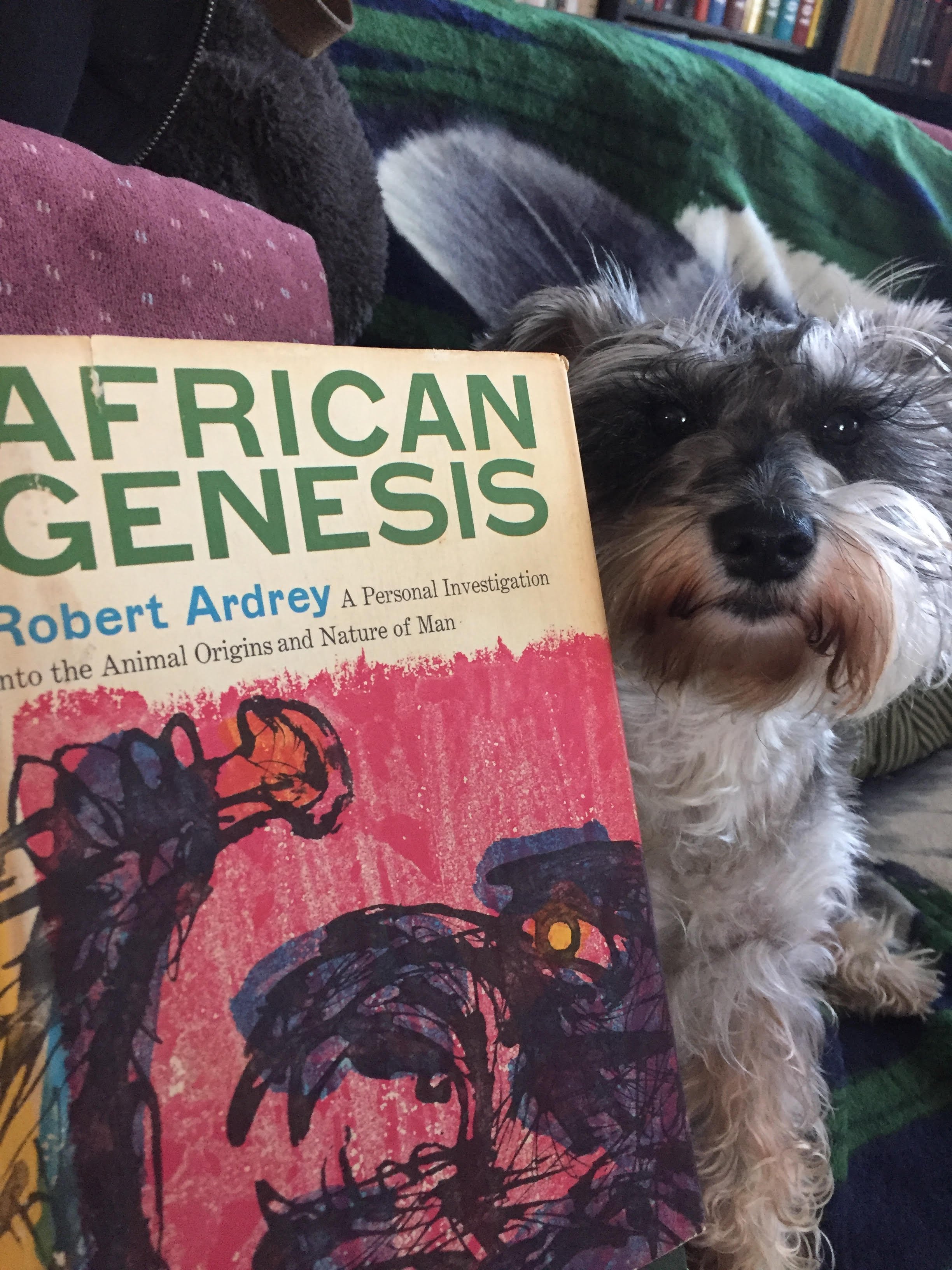

Stevereads: African Genesis

/Our book today is Robert Ardrey’s landmark 1961 book African Genesis: A Personal Investigation into the Animal Origins and Nature of Man, which in its very first line takes aim squarely at two vague and persistent notions: that modern humans originated in the Near East, and that those origins were peaceful, almost idyllic. “Not in innocence, and not in Asia, was mankind born,” Ardrey declares right at the beginning of his book. “Most significant of all our gifts, as things turned out, was the legacy bequeathed us by those killer apes, our immediate forebears.”

In the course of the book, Ardrey has one particular killer ape in mind: Australopithecus africanus, “the carnivorous ape of the high, ancient veld,” which was first discovered by Raymond Dart, who’s an odd and recurring character in the book. The central struggle Ardrey portrays so dramatically is the struggle to amend what he calls “anthropology’s appalling approach to the australopithecine problem” – amending it, that is, to show an Australopithecus africanus who carefully crafted and ruthlessly used weapons, hoarded food, and very likely made war in its own primitive way.

These elements went against the grain of common thinking in the discipline when Ardrey wrote his bombshell of a book, but it wasn’t mere iconoclasm that accounted for the wildfire popularity of African Genesis – there’s hardly a parallel to that popularity in our own science-denying era. The book was widely translated, widely discussed, widely debated … and there’s a good case to be made that it inspired an entire new generation of anthropologists, many of whom were eager to question the given wisdoms of the discipline.

But again, it wasn’t mere iconoclasm that gave this book wings; it was Ardrey’s soaring, passionate prose line. When he writes about modern humans (he immortally describes us as “bad-weather animals, disaster’s fairest children”), he strikes a note that still prompts a deep breath even now, 60 years after the book first appeared:

No creature who began as a mathematical improbability, who was selected through millions of years of unprecedented environmental hardship and change for ruggedness, ruthlessness, cunning, and adaptability, and who in the short ten thousand years of what we may call civilization has achieved such wonders as we find about us, may be regarded as a creature without promise.

Challenging given wisdoms always includes forcing well-established luminaries to eat a certain amount of crow, and Ardrey spent more than enough time talking with such luminaries while working on his book to know the size of some of the egos he was dealing with – and not to care all that much. “A scientist … has the right to be wrong,” he writes. “It is a right approximating an obligation, for if a scientist becomes more concerned with being right than with expressing the convictions of his judgement, then he violates a public trust.”

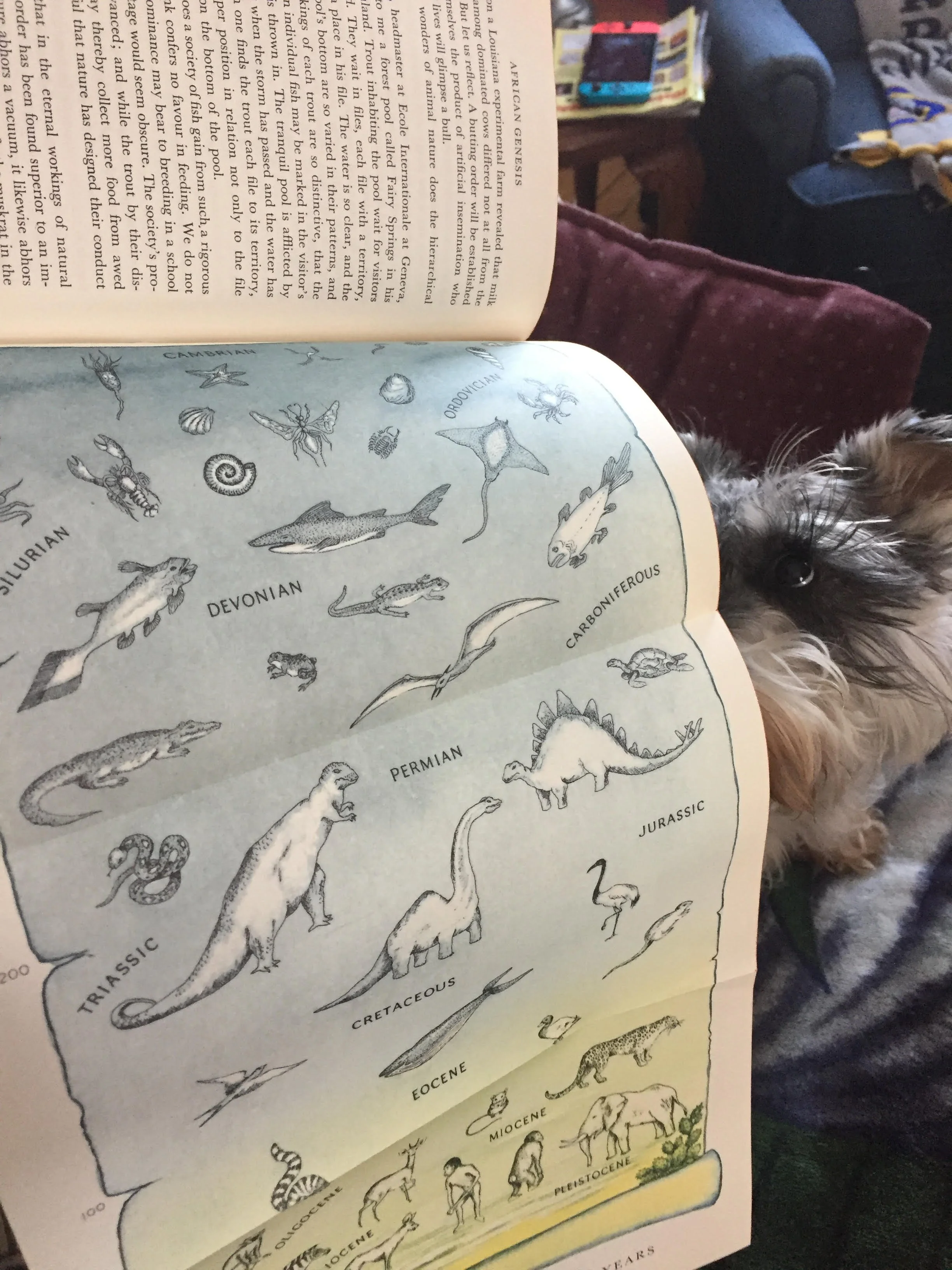

That 1961 edition of African Genesis included not only dozens of black-and-white drawings of various animals but also wonderful fold-out charts of deep-time chains of life as they were imagined at the time. The mass-market paperback of the book, which sold boatloads more copies that found their way into every used bookstore in the entire world, didn’t typically have those fold-out features, but the main impact of the book was undiminished. It’s ultimately a story about the wonder of science, and although the science might have advanced in gist and detail since the book first appeared (we have, among other things, genetic analysis that was undreamt of in Dart’s day), that particular exultant tone carries the day:

Man is neither unique nor central nor necessarily here to stay. But he is a product of circumstances special to the point of disbelief. And if man in his current predicament seeks a fair mystique to see him through, then I can only suggest that he consider his genes. For they are marked. They are graven by luck beyond explanation. They are stamped by forces that we shall never know.